The Saga of the Yellow-Billed Loon

A deep dive into that time my friends and I found a celebrity bird BEFORE it was famous.

Welcome to Owl My Children, a monthly newsletter where I relate an exciting bird anecdote and share an extremely cute clip from ABC World News Tonight (skip to the link at the end if you don’t want to read the whole thing!).

Happy spring! It’s raining in Pittsburgh, as usual, and I’m huddled on the couch while I write this newsletter. Despite the erratic weather, I’ve enjoyed the arrival of some of my favorite springtime birds this month. Common grackles are back in full force, roosting in my alley and sounding like the rusty chains of playground swings. The red-winged blackbirds often hang out with the grackles, doing their conk-la-ree! calls, and the cowbirds have also made a loud return, repeating their squeaky water-drip song from the telephone wires outside my living room window.

The most exciting thing that happened to me in March, though, was the ongoing drama surrounding the yellow-billed loon I mentioned in my last newsletter. I lost a full week of my life to this loon, so I can’t imagine writing about anything else!

The yellow-billed loon: initial discovery

I mentioned last month that while I was in Las Vegas with a group of friends from college, we went to the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve and found a yellow-billed loon. What I didn’t say is that I was an absolute MESS throughout the entire ordeal, because it was the rarest bird I have ever reported. Discovering it—and identifying it—was both a thrill and a nightmare. Also, that very same loon eventually BECAME A CELEBRITY.

Let me start at the beginning.

On February 26, our last day in Vegas, my friends Sarah, Laura, Ellie, and I went to the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve in the hopes of seeing greater roadrunners. I had spent the whole trip trying to see one, but we hadn’t had any luck so far.

The bird preserve itself was really beautiful and well maintained; there was a visitor center and check-in desk, where two nice staff members gave me information about where to look for roadrunners. The preserve is only open from 7 AM until 2 PM (which is an important detail for later!).

We arrived at around 10 AM and spent a couple lovely hours strolling around the ponds. We saw not one, but TWO roadrunners—we don’t know if they were fighting over territory or if they were potential mates. (You can see my photos on Flickr here.) Shoutout to Ellie, who had doubted her birding abilities from the start and yet spotted the roadrunners!

There were tons of waterfowl at the preserve, which made me nostalgic for Madison. As we passed one of the ponds, my friend Sarah called out that she saw a loon. I came over to look at it, and it instantly struck me as odd. It was a HUGE loon, and very pale in appearance. Then again, it might have only looked huge because it was surrounded by tiny buffleheads. It seemed to be in non-breeding / juvenile plumage. I used to see a lot of common loons in Madison, and this loon didn’t look like one of those. But I didn’t know what kind it could be.

(The then-mystery loon, which we now know is a yellow-billed loon. Photo by me)

I took a few pictures, lowered my camera, took a few steps to the left, raised my camera—and the loon was gone. Loons dive and can swim underwater for up to 5 minutes, so it’s common to lose track of them. We waited for it to resurface, but it never did (at least, not where we could see it). The waterfowl were also flying around, landing, taking off, flying around—it was chaotic. We thought the loon might have flown off when we weren’t looking.

I looked at eBird and saw that loons were not commonly reported at the preserve. I figured we could ask at the desk what kind of loon was on Pond 6. Surely another birder would have reported it.

It never crossed my mind that we would be the first and only people to see that loon. We had crossed paths with several birders during our time at the preserve, a few of whom turned up their noses at us when we said we were looking at a hummingbird. (They clearly thought we were novices. They also offered no information about the birds they had seen. Annoying.)

A little after 12 PM, we knew we needed to hit the road so that Laura and Ellie could get to the airport. Back at the visitor center, I asked, “What kind of loon are people seeing on Pond 6?”

The two staff members exchanged a look. “We don’t get loons here.”

They, too, seemed to think I had no idea what I was talking about. And who could blame them? “I have pictures,” I said, and on my tiny camera screen, I showed them the grainy photos I had taken.

They were shocked. They agreed that this was, indeed, a loon. But they also admitted they weren’t good at loons, because loons are rare in Vegas. One of the women got out her Sibley guide. She was convinced that we must have seen a common loon. I took her word for it—I mean, a yellow-billed loon would be too rare, and every other loon would have been much smaller, with a smaller bill. I didn’t want to push back on her advice; I appreciated how helpful and nice she was. So we went about our day.

(This is a photo I took in Madison of a common loon in non-breeding plumage. There are some key differences here: this loon has a very different bill—it’s darker, smaller, and not at all yellow. This bird also has a little white collar that cuts into the dark patch on the back of the neck. The loon we saw at Henderson had a blockier head and a dark spot behind the eye.)

Sarah and I dropped our friends off at the airport. We had a nice lunch. I tried to put the loon out of my mind. The clock ticked by; it was after 2 PM, which meant that the bird preserve was now closed for the day. We hadn’t submitted our eBird checklist yet.

We wanted to go to another park in the afternoon and see if we could find some Gambel’s quail, but first we got in the rental minivan and worked on our eBird checklist. I used my camera’s wifi to send a few of the photos to my phone, but I couldn’t brighten them without my computer. The more we looked at the photos, the less confident we felt about the common loon ID, but common loons were not listed as rare on eBird; they were merely “uncommon.” So, that felt better than reporting a super rare arctic bird. We submitted the checklist with the loon listed as a common loon.

Still, we felt a little uneasy, so we started looking up other loon possibilities. I studied my photos. Our loon had a thick, yellow bill. I couldn’t get over that bill.

Heart racing, I ran my photo through Merlin Photo ID (which is part of the free Merlin app!). When the results loaded, I moaned in fear. The app aligned with what I suspected: it suggested that this was a yellow-billed loon.

A yellow-billed loon had never been reported at this bird preserve before. The last time one was seen near Vegas was in 2018 at Lake Mead. It would be rare for Clark County, and rare for the entire state of Nevada.

A digression into the eBird review process

When you add a bird sighting to eBird, it gets automatically categorized as either common, uncommon, or rare. If you eBird a rare bird, you are required to provide more information about the sighting. The best thing you can provide is a photo (or several), but you should also add information about where you saw the bird and why you’ve ruled out all the other possibilities.

There are 3 reasons a bird might be flagged as rare: 1) this bird isn’t usually found in this region; 2) it’s the wrong time of year to see this bird; or 3) you’ve reported a “high count,” meaning that the number of birds you saw of this particular species is unusual for the time and/or place. (You can read more about the nuances here.) When we went to add the yellow-billed loon to our eBird checklist, it flagged as rare.

One TERRIFYING thing to note: If you eBird a rare bird, it will get picked up in eBird’s Rare Bird Alert feature. This means that all the intense birders in your region who have subscribed to alerts will get an email notification about your report. (You can set these alerts to a daily cadence, or even hourly. I did the hourly cadence for a while—it was a LOT of emails.)

A local eBird reviewer must also review all the rare bird reports in their area. If they confirm the report, it will show in the Rare Bird Alert email as an all-caps CONFIRMED sighting. If they think you’re wrong, they will not confirm the sighting and they might send you an email asking you to change your report.

So here was the dilemma: If we kept our checklist the way it was, with the loon listed as a common loon, it wouldn’t get sent out in an email blast to all the local birders. It also wouldn’t get flagged for a local reviewer to confirm. Without a reviewer’s input, we might never know with 100 percent certainty what species this loon really was. And local birders might not have a chance to see the loon before it was too late.

If we changed it to a yellow-billed loon, it would be sent out in a Clark County Rare Bird Alert as well as in the Nevada Rare Bird Alert. Everyone would immediately see our description and photos, and—if we were wrong—they’d think, “These people are idiots! This isn’t a yellow-billed loon! OBVIOUSLY.”

It’s happening

Since the preserve had already closed at 2 PM, Sarah and I knew we had time to make the decision. No one would be able to go out there and re-find the loon until 7 AM the next day, anyway. So I texted my friend Megan, who is a much better birder, and sent her my pictures. She was convinced it was a yellow-billed loon. Meanwhile Sarah researched yellow-billed loons and found a few helpful articles like this one, which notes that young yellow-billed loons have a “prominent post auricular spot.” Just like ours.

After hours of waffling and trying not to chicken out, we finally decided to go for it. A little after 6 PM, I edited our checklist, changing the “common loon” designation to “yellow-billed loon.”

(Another photo of our yellow-billed loon, by me. Thank you, Sarah, for your infinite patience and for driving the minivan while I googled loons in the passenger seat.)

We went to the airport and got on our separate planes. I took a red-eye back to Pittsburgh. The morning of February 27, after an hour or two of trying to catch up on sleep, I opened my phone to a text from Megan: IT’S HAPPENING.

Thanks to our checklist, four other birders had gone out to the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve that morning and taken photos. They all agreed that this was indeed a yellow-billed loon. They reported that the loon flew off at around 7:45 AM.

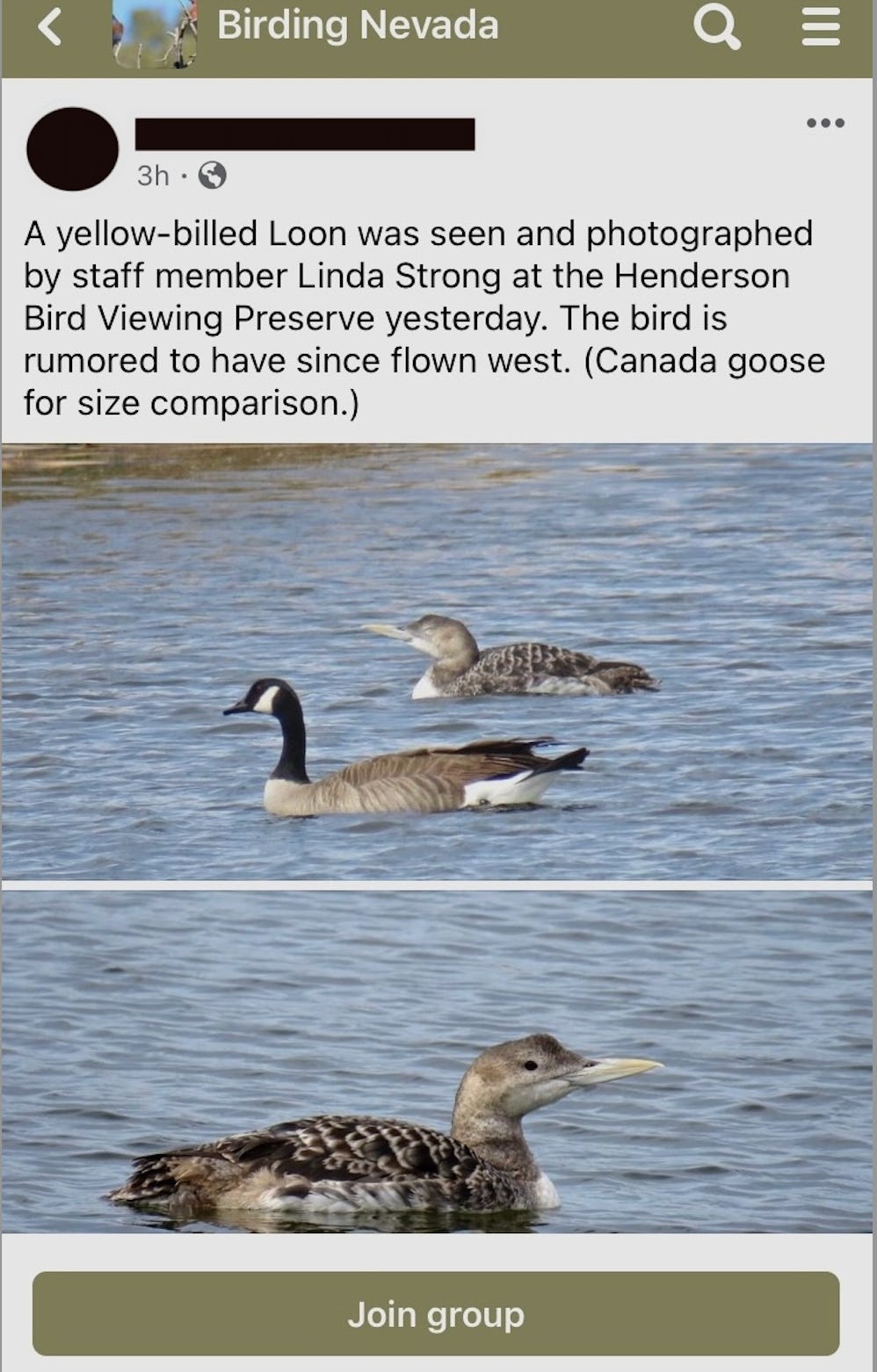

Then, on the Birding Nevada Facebook group, several folks noted that one of the women who worked at the preserve—Linda, who had taken out her Sibley guide to help me—had gone out to the pond after we left on Feb. 26. Her photos were so good that everyone knew, without a doubt, this was a yellow-billed loon and not a common loon.

(Screenshot taken on Feb. 27 of the public Birding Nevada Facebook group. Loon photos by Linda Strong. Special thanks to my friend Ben for alerting me to the existence of this group!)

After waiting a few days, our rare bird sighting was officially CONFIRMED on February 29. This means that now, when you use the Species Map feature on eBird to see all the historical reports of a particular species, you will see our sighting as the first yellow-billed loon sighting ever at the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve.

(Screenshot of the eBird Species Map feature for yellow-billed loons. The red markers indicate sightings in this calendar year; the blue markers indicate sightings in older calendar years.)

The loon wasn’t seen again…

Until it showed up on Saturday, March 2, at the Bellagio.

Arrival at the Bellagio

I told bragged to a few of my birding friends that I’d seen a yellow-billed loon in Vegas, so they were very nicely following the situation on eBird and Facebook, waiting to see who else found the loon and where it ended up. So it was my friend Caitlyn who saw on eBird that the loon had ended up in the Bellagio fountain on Saturday. After she texted me about it, I started following the whole saga on the Birding Nevada Facebook group, where there were LOTS of opinions about the loon. Two camps emerged: The camp of people who were pumped to find a rare loon at such an easily accessible place and who were taking lots of closeup photos, and the camp of people who were worried about whether or not the loon would survive.

Interesting fact about loons: They “need a large expanse of open water to take off. They take a long running start, using both their wings and legs, to build up enough speed to become airborne” (from David Allen Sibley’s What It’s Like to Be a Bird, p. 21). Their legs are in a really weird, far-back position on their bodies, so they can hardly walk on land, much less run. This means that sometimes loons land in a stretch of water that’s too small for them, like a pond, and they get stuck. They can also get stuck in lakes that have begun to freeze, when the ice reduces the size of their runway. And sometimes loons accidentally think fields are ponds, and they come down for safety during a storm, and, well—you get it.

So when the loon landed in the Bellagio fountain, the question of the size of the runway was the first concern. The next concern was food. Loons eat fish, and no one was sure if there were fish in the fountain. One person posted to ask if there were goldfish in the fountain, and if not, should they bring some over? (Interestingly, the people at the Henderson Bird Viewing Preserve told me that there are no fish in their ponds, so they didn’t expect the loon to stay very long. If the loon hadn’t eaten at the ponds on Feb. 26 or 27, did it manage to find dinner between the preserve and the Bellagio? Or had it gone almost a full week without eating?)

For the next few days, the loon remained at the Bellagio, and people on Facebook grew more concerned, waiting to see if it would be able to take off. There was some discussion about how a recent storm must have blown the loon down; now that the weather was better, shouldn’t it take off again? A few folks wanted to rescue the loon and tried to get some rehabbers involved, looping in the Nevada Department of Wildlife. But the rehabbers didn’t want to interfere if the loon seemed healthy and could fly on its own. They recommended that everyone wait and see what happened.

One final fear emerged: What about the fountains? The Bellagio fountain show goes off every 30 minutes between 12 PM and 7 PM, and every 15 minutes from 7 PM to midnight. The loon got lucky when it landed there: the fountain show had been put on pause for routine maintenance. But everyone worried that, if the show were to resume on Tuesday, March 5 as the Bellagio intended, the loon might get blasted by a spray of water. So the Facebook folks organized an effort to talk to the Bellagio staff about pausing the show.

And the Bellagio listened!

Which is when the loon became national news.

Loon makes headlines

The loon first appeared on Tuesday, March 5 in the local Vegas newspapers. For example, in the Las Vegas Review Journal, there was an article titled “Latest Strip residency: Rare bird finds home at Bellagio.” Then the loon showed up on ABC and NBC: “Rare bird shuts down iconic Las Vegas fountain” and “Rare bird that 'found home' in Fountains of Bellagio pauses popular Vegas water show.” The Bellagio posted about the situation on social media: “We are happy to welcome the most exclusive guests.”

Fountains off, the Facebook group breathed a sigh of relief, except: Why wouldn’t the loon fly away? Was it stuck? Was it starving? The loon remained at the Bellagio through March 6, and throughout that entire time, no one saw it eat anything.

I have to admit, I was worried that our rare bird success story was about to turn into something traumatic. I often feel this way when a very rare bird is reported nearby. Do I go see the rare bird while it’s here, even though it’s lost and might not make it back home? Even though it might die?

Send in the biologists!

On the morning of March 6, a biologist from the Nevada Department of Wildlife captured the loon, then released it at an undisclosed body of water. The loon seemed totally healthy and did a weird loon hop-flap into the lake, where it has not been seen again, as far as I can tell.

The Review Journal and NBC updated their stories with the good news; the loon was even on ABC’s World News Tonight! My heart is full!

Here are my takeaways from this experience:

I’m glad we trusted ourselves and eBirded the yellow-billed loon, even though it was rare, even though we could have been wrong. If we hadn’t done that, maybe no one else would have seen it at the preserve; maybe it would have taken a longer time for people to see it at the Bellagio and recognize it for what it was. (Or maybe not. Still, it’s a nice thought.)

I guess social media can be good for something???

I’m sorry this newsletter is so long. Thank you to all my friends for putting up with me as I stressed about this loon. If you want to see photos of any of the other wildlife I saw in Vegas (and there were some good ones! Vermillion flycatcher! Common ravens acting like my cat Otis! Bighorn sheep!), here’s my album on Flickr.

Loon love,

Holly